To own the nickname, “Mr. Patriot” might just say it all. Or perhaps his other nickname is equally as telling: “The Duke,” a name that is stamped onto NFL footballs today.

Combine the two and maybe Patriots Hall of Famer Gino Cappelletti should simply be called Mr. Football. That’s what he was here in New England and even remains such in emeritus as he approaches his 87th birthday this month. He is the oldest living Patriots Hall of Famer and he represents a connection to the Patriots first playoff team back in 1963 – 58 years ago.

His accomplishments and honors certainly propelled him into the Patriots Hall of Fame, but are also worthy of Pro Football Hall of Fame consideration.

Cappelletti was an original Boston Patriot in 1960 and played through the upstart American Football League’s entire existence leading into the AFL merger with the National Football League in 1970. He is the AFL’s all-time leading scorer and third on the Patriots scoring list with 1,130 points. He is a member of the AFL All-Time Team after leading the league in scoring five teams, including a record 155-point season in 1964, one after which he became the first Patriots player to be honored with a league Most Valuable Player award. That 155-point season remains fourth in Patriots history behind a 158 and two 156 point seasons by current kicker Stephen Gostkowski in 2013, 2014 and 2017. He was a five-time AFL All Star.

But none of that came easy.

After stints playing in Canada and his service to the United States Army, Cappelletti found himself home in Minnesota in 1959 without a job playing football. He had been an All-Big 10 second team selection at the University of Minnesota, but wasn’t drafted by an NFL team in 1955. So he toiled north of the border before heading back to his home state with no football left to play.

Then the birth of a new league provided new hope, and Cappelletti sought another chance to play. He simply called Boston Patriots head coach Lou Saban and asked to tryout. So Cappelletti showed up in Amherst, Mass., along with 125 other hopefuls. His willingness to do anything, play anywhere and work hard doing it earned him a roster spot.

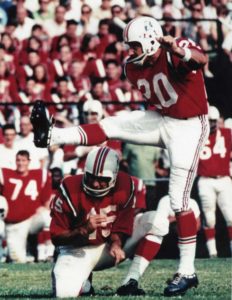

He began his Patriots career as a kicker and defensive back, but moved to wide receiver during the 1960 season. Back then, if Cappelletti was only kicking, he may have found himself with a ticket back to Minnesota. That first year, he kicked 30 extra points, eight field goals, caught one pass and intercepted four. One season later, in 1961, he was the Patriots leading receiver and even threw and completed a 27-yard touchdown pass.

In 11 seasons, The Duke made 176 field goals and 342 extra points while hauling in 292 passes for 4,589 yards and 42 touchdowns. To put those receiving numbers in perspective, one only needs to look at the Patriots record books. He remains 11th all-time in receptions, 10th in receiving yards, fifth in receiving touchdowns and eighth in yards per catch with 15.7. Not bad for a guy who played in a different era when the passing game paled in comparison to what it has become in today’s pro game.

Cappelletti, though, is reluctant to focus on his statistics, his nicknames or his accolades. Sure he remembers a game-winning, last-second field goal to beat Buffalo at Fenway Park in 1964, but he prefers to speak about his team.

“Our teams weren’t about one or two big stars,” Cappelletti said recently. “We were about the team and that’s it. It was a tough situation back in 1960 when the AFL was just starting, but we had great people and those early teams were important to football in New England.”

None were more important than the 1963 team that established credibility for the local club trying to make it in an area that had rooted for the NFL’s New York Giants as its “home” team.

“Our 1963 team went to Buffalo and had to win on the road to get to the AFL Championship,” Cappelletti recalled. “That was a good rivalry like it is today, but we won [26-8] and went out to play San Diego for the championship. San Diego had a great team, a better overall team than we had, and they beat us out there, but I think reaching the championship really helped establish professional football here.”

Boston lost that 1963 championship, 51-10, but reaching the title game captured the attention of local football fans. “I do think that team changed football in Boston,” Cappelletti said. “We were growing as a team on the field and that helped it grow off the field as well.”

Cappelletti was critical to that growth whether or not he admits it. He is one of only 20 people that played all 10 AFL seasons along with teammates Babe Parilli and Jim Lee Hunt.

Hunt, like Cappelletti, played all 10 with the Patriots, but The Duke is one of only three that played in every AFL game in which his teams played. George Blanda and Jim Otto were the other two.

Cappelletti was around long enough to officially establish the Patriots in their permanent Foxborough home when he scored the first points at the newly constructed Schaefer Stadium in a 1971 preseason game against the Giants. His playing career ended before the 1971 season officially kicked off.

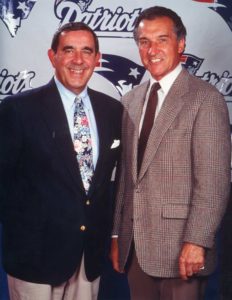

He spent most of his post-playing days calling Patriots games alongside his friend,  radio partner and now fellow Patriots Hall of Famer Gil Santos. Together, Santos and Cappelletti described Patriots games for 28 seasons and 585 games including six Super Bowls.

radio partner and now fellow Patriots Hall of Famer Gil Santos. Together, Santos and Cappelletti described Patriots games for 28 seasons and 585 games including six Super Bowls.

If that’s not enough, Cappelletti also coached special teams for three seasons from 1979-1981 under head coach Ron Erhardt.

Today, he plays some golf, relaxes and spends some vacation time at a family home on Kiawah Island in South Carolina. He still appears around Gillette Stadium and The Patriots Hall of Fame presented by Raytheon from time to time while adorning his red Hall of Fame blazer.

Cappelletti was just 26 when he arrived in Amherst, Mass., for a tryout. He will be 87 on March 26th. That’s a 61-year connection to the Patriots, and all 61 were filled with the class that earned him the nickname “The Duke.”

But after more than half a century connected to the club, Mr. Patriot might be the nickname of choice.

“Oh heavens no,” he said humbly. “I don’t know even where that came from.”

He doesn’t have to know. We do.